In a recent article, the Washington Business Journal noted that GSA will struggle to take full advantage of the current tenant’s market before the pendulum swings back to the landlord’s favor. This, despite the fact that GSA has many leases expiring in the near term, creating immediate opportunities to negotiate new low-cost contracts. I was quoted as saying (with dubious grammar): “The window is closing on the GSA … Part of the problem is that at no point in GSA’s history has the agency been able to do not even half of the volume of leasing that needs to be done here.”

Plus: Which way the political wind blows | What is an OA?

This comment, sitting alone without context, could be interpreted as a cranky indictment of GSA’s leasing capability. It was wasn’t intended as that, though the statement is mostly correct. It will take time for GSA to work through the massive pileup of near-term lease expirations; therefore, the government will not be able to take full advantage of current market conditions.

Also: The Key Sustainable Products Initiative | GSA occupancy of new buildings has dwindled

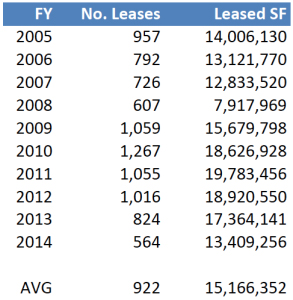

Let’s take a look at the facts. The table below shows the volume of new leases GSA has “completed” in each of the past 10 fiscal years. See the note at end of this article to understand how lease commencements are used as a proxy for completed leases.

When you look back at this 10 year stretch, GSA has completed an average of 15.2 MSF of new or replacing (i.e. “renewal”) leases annually. In the best of these years (2011), GSA completed 19.8 MSF of new or replacing leases. The total volume scheduled to expire in FY 2015 is 29.4 MSF. That’s 87 percent more than the GSA’s average leasing volume and 48 percent more leasing than GSA accomplished in its best year. Maybe I’m guilty of a little hyperbole as quoted by the Washington Business Journal, yet the gist of my statement holds true.

So, what happens to the leases that GSA does not negotiate anew? As evidenced from GSA’s own data, most leases simply extend at the end of their terms (and unfortunately sometimes that method of extension is holdover). The primary reason for the high volume of extensions is overwhelming workload paired with budgetary and planning challenges associated with edicts to freeze and ultimately reduce the footprint — actions that typically require significant rethinking of the workplace.

Of course, we should not expect the complete eradication of lease extensions. When used strategically, extensions have a useful purpose, allowing for future consolidation or realignment of facilities. Yet, as a practical matter, the government mostly relies on extensions as a form of triage. The great irony is that extensions provide only a modest shortcut through the procurement process. Even short-term extensions are presented with a bureaucratic obstacle course that takes time, sustained effort and limitless patience.

Can GSA ever catch up to its workload? The answer is yes, but it will take a while. If you do the simple math — assuming you want to achieve “normal” leasing flow where, say, 90 percent of leases are new/replacing and only about 10 percent are extensions (a fantasy that exists only in the slumberland musings of the nation’s largest federal property investors) and the remaining leases roll forward in a bow wave to future years — then it would easily take about five years for GSA to get its workload fully under control. To put that in political terms, it will take the remainder of this presidential administration and the entire elected term of the next one. A lot can happen in the interim.

A note regarding these numbers

We use the word “completed” to generically describe leasing volume based upon lease commencements. We don’t actually know when all of these leases were originally executed, which would have been our preferred standard. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to estimate lease execution dates based upon lease commencement because sometimes the government will execute leases years in advance, as in the case of build-to-suit projects, or after commencement in the case of holdovers. Given the limits of GSA’s publicly available data, “completed” (i.e. commenced) leases will have to suffice.

A second note regarding these numbers

Some would argue that any analysis of GSA leasing capacity should focus on the number of leases GSA completes instead of square footage (looking at the number of leases completed instead of square footage yields a slightly more hopeful outlook, by the way). There’s pretty solid logic to that since small deals are subject to the same cumbersome procurement process as larger ones, despite GSA’s efforts to implement streamlined procedures. However, the largest leases must endure congressional prospectus approval and a towering hierarchy of scrutiny. It doesn’t take many of these to really gum up the works, so we look at square footage as the preferred measure.

Kurt Stout is the national leader of Colliers International’s Government Solutions practice group, which provides government real estate services to private investors and federal agencies. He also writes about federal real estate on his Capitol Markets team blog. You can contact Kurt by email or on Twitter.

Colliers Insights Team

Colliers Insights Team

Michelle Santos

Michelle Santos