Welcome to 2016! What a lovely start to the year. Nothing like a little stock market correction to remind us that the holiday season is over. The jitters actually started just after Christmas but gained momentum after the Chinese markets plunged with the first trading days of the new year.

How concerned should we be? Some, but not overly. We should always take notice of extreme market volatility for potential nuggets of economic intel, but consider this my semi-annual reminder that financial markets are not reliable predictors of economic vitality. There’s just too many false positives overstating the significance of normal volatility. In the famous words of economist Paul Samuelson: “the stock market predicted nine of the last five recessions.”

Wall Street and other western financial markets have been (over)reacting primarily to events in China. The slowdown in the world’s second-largest economy is real and worrying, with huge impacts on the global economy and particularly in emerging nations. China’s investment-focused growth in recent years has supported the economies of many developing nations with their massive commodity imports, and China is the top trading partner for many. China’s commodity imports have been dropping not only because its growth is slowing, but also because China is transitioning to a more consumer- and service-based economy that requires less petroleum and other natural resources. I view this transformation as a fundamentally positive step in the maturing of China’s economy, but you can be sure the journey will be turbulent, inviting lots of second-guessing from markets and analysts at every bump.

Fears about the likely impacts on the U.S economy seem overblown. To review: Exports account for only 13% of our economy and China for less than 8% of that, or just 1% of our economy overall. And it’s not like China is imploding. In fact, China is still growing strongly, at more than twice the rate of U.S. growth and relatively constant on an absolute basis.

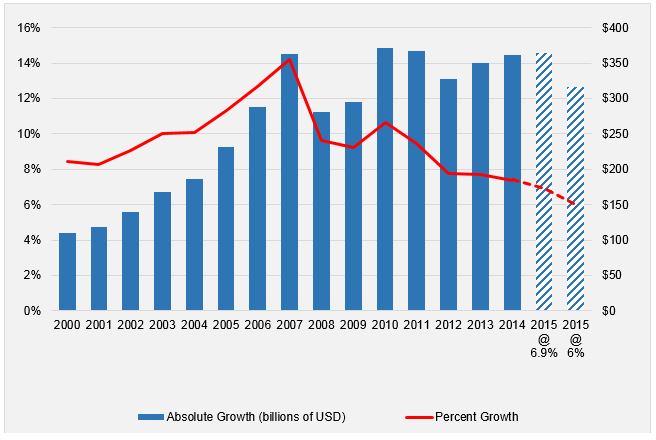

In the first chart below, the red line shows China’s growth rate slowing from about 10% in 2010 to 7% in 2014. But the blue bars show the growth in absolute terms (U.S. dollars), which has been more constant. Which makes sense: as the economy gets larger, it’s hard to sustain the same growth rate. With the Chinese economy growing only 6.9% last year per official statistics, the absolute growth was about the same as in 2007, when China grew by 14% and 2010, when the economy grew by more than 10%. And if actual growth really slowed to only 6% – as some economists estimate – the growth in dollar terms would be about the same as in 2012, when China grew by 8%.

So, slowing growth, but still growing. Strongly.

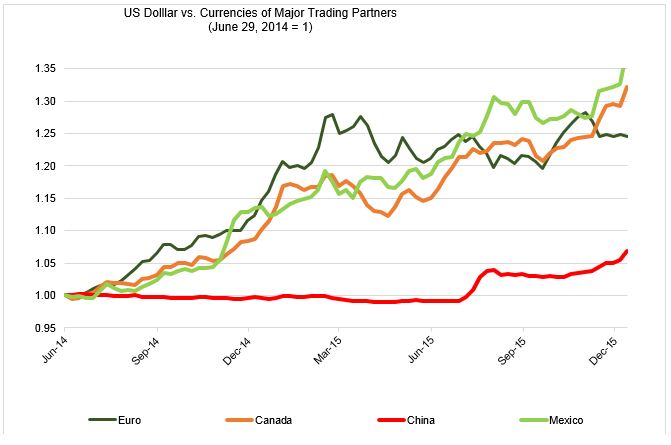

The other major worry as it relates to the U.S. economy concerns the devaluation of the yuan* relative to the dollar. Here again, the concerns are overblown: Beijing tightly controls the trading range for the yuan, and they are not allowing the value of the yuan to move all that much. (There is a growing spread between the “offshore” value, which they cannot directly control, and the “onshore” rate, but it is still only about 2% or so.) In the second chart I show the dollar vs. the currencies of our top four trading partners (in order): Canada, China, Mexico and the Eurozone. The dollar has appreciated between 25% and 35% since mid-2014 against the loonie, peso, and euro. Meanwhile, the yuan, in red at the bottom of the chart, is up less than 7%.

It’s true that historically that yuan’s value hasn’t moved much or quickly, making the recent movements all the scarier for some analysts who worry about what this portends about “real” weakness in the Chinese economy and Beijing’s ability to guide their economy. Perhaps. And for extremely risk averse traders, a world of worry. For the rest of us: the evidence on the ground seems less dire.

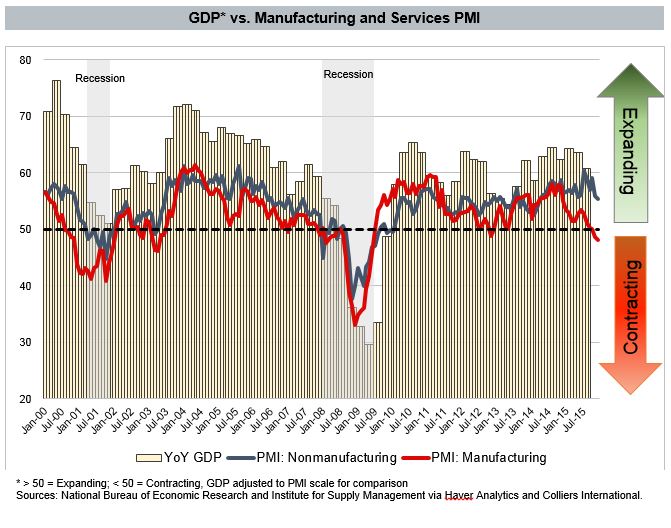

Beyond the market drama last week, bearish economists point to the Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM), which has been falling and has been below 50 for the past two months. This indicates the sector is contracting, as shown in red in the next chart. It’s the first time the index has been below 50 for two consecutive months since the recession. Meanwhile, PMI for non-manufacturers – basically the much larger service sector – is at a still-healthy 55 though also falling.

Does that suggest we’re heading to a recession? I don’t think so. First, although manufacturing is obviously an important sector, it represents only about 15% of our economy. Second, the index periodically falls below 50 and it usually does not presage a recession.

More importantly, other indicators tell a much different story. We added an average of almost 300,000 jobs a month in the fourth quarter, not the marker for a recession. The financial health of consumers, which account for more than two-thirds of our economy, is stronger than at any point since the recession and continues to strengthen. And to get wonky for a moment: the yield curve, which is perhaps the single best predictor of recessions, is still upward sloping with the spread between the 10- year and 2-year bonds above its long term average. (A downward sloping curve, in which long-term rates are below short-term rates, suggests investors discount near-term economic prospects.)

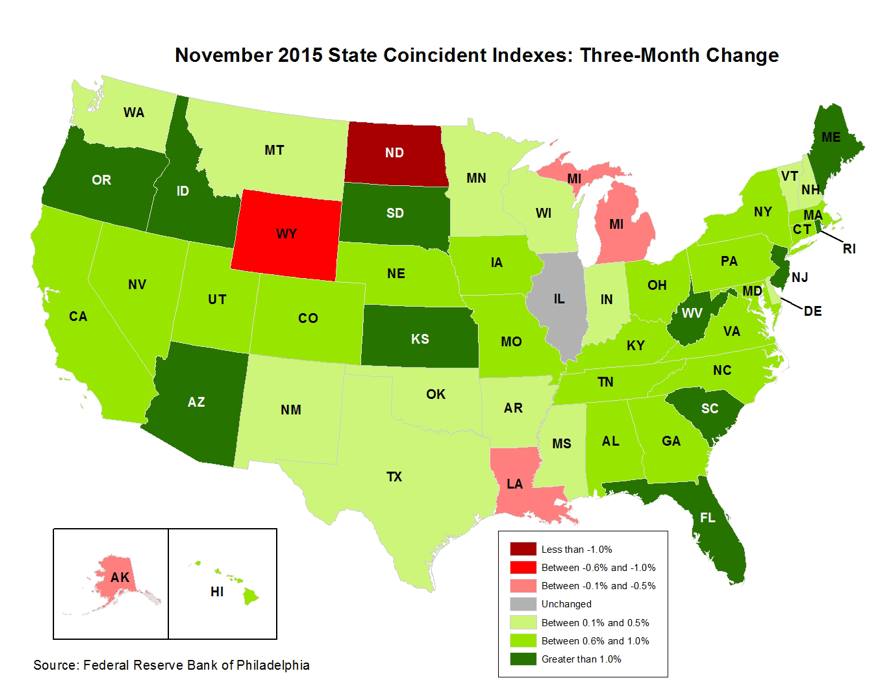

Finally, the leading economic indicators tracked by the Philadelphia Fed are strongly positive. The map below shows the states that are growing – based on jobs, incomes, electricity usage, hours worked, and unemployment – and almost every state is growing.

That said, there’s still plenty to be concerned about: rising geopolitical risks, capital flight from China and the risk of currency contagion in the emerging economics. There’s a world of hurt in the oil patch, which has yet to be balanced by the expected positive of low gas prices for the rest of the economy. And we face mounting headwinds from the global slowdown and rising dollar. Overall, expect U.S. fourth quarter GDP to fall short of recent averages, which will prompt the bears to call the impending onset of recession as they have at least annually since the recovery began.

Of course, the expansion can’t last forever, and there’s little doubt we’re closer to the end of than the beginning. The 70 months of expansion is already longer than average . But we’re not ready to wave the white flag just yet. Remember that economies rarely just run out of fuel or “die of old age” in the words of Beryl Sprinkel, President Reagan’s chairman of Council of Economic Advisors (now there’s a winning trivia answer!). Rather, recessions are generally caused by an exogenous shock and/or asset bubbles in combination with restrictive Fed monetary policy, typically thought to be where the real federal funds rate (FFR) exceeds 2%. Despite the modest December hike, the real Federal Funds rate is still negative, and given the Fed’s stated intensions and anticipated moderate growth prospects, future Fed hikes are likely to be restrained — and the real FFR is likely to remain negative — for the next couple of years.

So, no, we’re not about to slide (or plunge) into recession. Given the rising risks and headwinds, we can expect growth in 2016 to disappoint and even underperform compared to 2015, but the sky isn’t falling. Chicken Little needs to chill.

*Technically, China’s currency is officially called the “renminbi” while the “yuan” is the unit of account. The two are used interchangeably in most circumstances.

Colliers Insights Team

Colliers Insights Team

Aaron Jodka

Aaron Jodka